Nuclear must continue to account for at least one-quarter of the European Union's energy mix if the region is to meet its 2050 emission targets, a report commissioned by Foratom has concluded.

The European Commission is expected to set a strong decarbonisation target of up to 95% by 2050 in its strategy for long-term EU greenhouse gas emission reductions to be issued on 28 November.

Foratom, the European nuclear trade body, commissioned FTI-Compass Lexecon Energy Consulting to produce a study "to provide fact-based evidence to the policy debate".

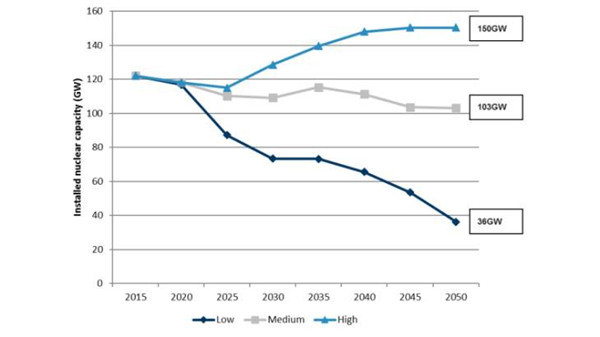

The study - titled Pathways to 2050: role of nuclear in a low-carbon Europe - analyses the potential contribution of nuclear generation towards a low-carbon European economy based on three nuclear capacity scenarios: low (36 GWe), medium (103 GWe) and high (150 GWe). Foratom said the scenarios have been designed to cover a range of possible future developments for nuclear in Europe. Each scenario assumes a 95% decarbonisation of the energy mix in 2050, compared with 1990, as well as growth in electricity demand to about 4100 TWh from the current 3100 TWh.

The nuclear capacity scenarios used in the report (Image: FTI-CL Energy)

The study also considers the European nuclear sector's contribution to several key energy policy objectives, namely security of supply, decarbonisation and sustainability, and affordability and competitiveness.

"Decarbonising the European energy mix by 2050 while maintaining security of supply will require the mobilisation of all low-carbon, secure and cost-effective power generation sources," the study says. "An efficient power sector transition towards low-carbon technologies will need to account for both carbon emissions and other environmental impacts, including air pollution, impact on land use and resource use."

The study concludes that, in the short- to medium-term, the continued operation of Europe's existing nuclear power plant fleet will help it meet emission targets and would "avoid the temporary increase of the emissions that could risk locking in fossil fuel investments". In the longer term, nuclear energy can support variable renewable sources by "providing proven, carbon-free dependable power and flexibility to the system and reducing the system's reliance on yet unproven storage technologies".

The study says that nuclear new build will need to "demonstrate significant cost reductions to succeed in liberalised European power markets". In addition, "the timely development of storage technologies including the reduction of their cost and/or flexible operation of nuclear will be critical to ensure the complementarity of nuclear and variable renewables." It suggests the power market should be designed to reward the "system value of dependable and flexible resources", and to provide stable long-term investment signals.

"The study finds that achieving the European emissions targets in a scenario with a significant early phasing out of nuclear plants would prove more challenging and increase costs for customers," said Fabien Roques, executive vice president of FTI Compass Lexecon Energy. "The results demonstrate how nuclear can contribute to an ambitious decarbonisation of the European economy."

Yves Desbazeille, director general of Foratom, said: "Nuclear power is a low-carbon technology which is available today. Instead of focusing on technologies which have yet to be proven, both technically and financially, the EU should be promoting those which can already provide the low-carbon electricity which Europe needs. Only by doing so, does the EU stand a chance of meeting its 2050 decarbonisation targets."

The 128 nuclear power reactors (with a combined capacity of 119 GWe) operating in 14 of the 28 EU member states currently account for over one-quarter of the electricity generated in the whole of the EU. Nuclear accounts for 53% of the EU's carbon-free electricity.

The global nuclear industry has set the Harmony goal for nuclear energy to provide 25% of global electricity by 2050. This will require trebling nuclear generation from its present level. Some 1000 GWe of new nuclear generating capacity will need to be constructed by then to achieve that goal.